Swindon in the 1950s

It seemed to rain a lot in Swindon in the ‘fifties,

And not only on Sunday afternoons,

Which was partly why our only movie starWas the alliterative Diana Dors -

And she was no better than she should be –

You could read about her in the News of the World,

The pages wrapped around your bag of chips,

While you listened to the echo of your footsteps,

As you walked home through the empty lamp-lit streets;

Mr Morse still delivered our milk by horse and cart,

We walked to the gas works, with an old pram,

To bring home the coal rather than a baby;

You could train-spot for free on the Milk Bank,

And fall asleep to the comforting sound

Of trains buffering up and shunting,

Or steaming and whistling through the night;

Swindon Town played in Division Three (South),

And liked life near the wrong end of the table;

Arnold Darcy, signed from Accrington Stanley,

Was not only fleet-footed on the wing,

But a painter and decorator too;

Unlike the likes of Jimmy Gould and ‘Bronco’ Lane,

Banned from the game because they fixed matches –

But wouldn’t we have lost anyway?

For a boy, the launching of the Sputnik

Seemed less important than the Munich air disaster,

While farms in Swindon became housing estates,

London accents became more prevalent,

And whenever the local paper reported on a crime,

My dad said, ‘Cockneys again’,

Even though he had been born in Notting Hill.

Some shops had some sort of conveyor belt

That ran around the ceilings

To carry the change,

Like the Co-op when we bought our duffel coats,

It fascinated me but even then it seemed archaic;

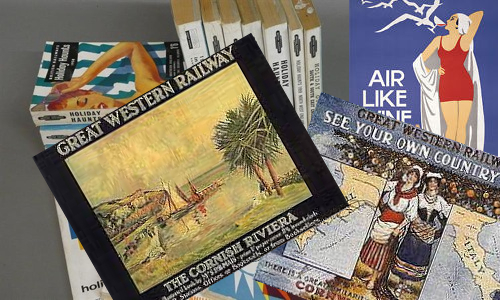

Express trains still evoked the 30’s -

‘Holiday Haunts’ on the GWR -

The Bristolian; the Capitals United;

The Cheltenham Flyer; the Red Dragon;

The Merchant Venturer; the Cornish Riviera Express;

Diesels started to appear with names like Ark Royal –

The Warship class celebrated our island heritage -

While experimental German gas turbine locos

Sped to Paddington, with a gentle reminder

Of the cultural confusion caused by the Cold War,

There might be pillboxes where you watched the trains go by,

But Germany, recent enemy,

Was now, partly, West Germany and an ally,

Even if still the foe in film and field

And war games in the streets

(‘I think I’ve copped one, corp’),

1930s art deco diesel railcars

Were lined up in sidings at Rodbourne Cheyney,

And you could stand by chocolate and cream railings,

Covered in dog rose and blackberries,

To watch sleepy saddle or pannier tank locos,

Making their interminable way

As station pilot, up and down all day,

From works to yard to station to siding;

A lot of houses seemed to be chocolate and cream,

Or varnished or Brunswick green,

Front windows had net curtains,

Back gardens had old guards’ vans for sheds,

Which is where your dad went on Sundays,

While you dressed up in your Sunday best,

And went into the front room for the once a week visit;

Your mother cooked roast beef and all the trimmings,

Listening to Family Favourites

‘What’s the weather like over there, BFPO 40?

Here’s Petula Clark with ‘Sailor’.

You never had visitors during the week,

Apart from the insurance man

(Wesley and General),

Who, like so many other men of his vintage,

Could seemingly whistle and smoke simultaneously.

Irony was unknown,

Three ducks on a wall were everywhere,

Mums knitted fair-isle pullovers

From black and white books of patterns,

Cars queued for petrol in 1956 -

The Suez Crisis –

You played marbles and conkers in the autumn,

Went apple-noggin,

You got fog and smog in November,

When you pretended that you were in Just William’s gang,

Looking for movement in the net curtains,

If you kicked a ball into a neighbour’s garden,

Or were playing knock door runaway.

You played football in and across the road,

Street signs constituting the goals,

Or when out in the fields and mud,

Your first boots were big and brown,

But not as heavy as the damp leather football.

You could join the Swindon players

As they trained in Shrivenham Road,

Next to the iron bridge,

Which meant that you could play football,v Collect autographs,v And get train numbers,

All simultaneously;

You didn’t need a watch,

The railway hooter let you know when to get up,

When to have your dinner and when to get the tea ready,

And if you stayed out late train spotting

(‘Bags I’m the British’),

By the pill box near the Bunkie bridge,

The Highworth branch line workers’ special

Let you know when you’d better get back,

Back to that time when you were the first baby

To be born at home in a pre-fab –

My mother was interviewed by the ‘Adver’,

And said she’d never want to live in a brick house again,

The Ministry of Housing came down to take pictures of our home:

We were a model for the country,

As was the estate at Pinehurst,

All the families who moved in early into Beech Avenue,

Were the families of World War Two servicemen and women,

And there were schools; bobbies on bikes;

A clinic where you got your free milk and juice …

We had a friendly old doctor, by name Dr Liechenstein

(Who knows what horrors he’d escaped),

The streets were named after trees,

Or after generals,

Homes sort of built for heroes,

There was an area called The Circle,

With a library, a sort of village green,

And the crumbling residue of the war,

While the row of shops had a butcher’s,

A fish and chip shop,

A barber named Watkins

(Short back and sides),

A grocer’s called Haskins

(Packets of Cheeselets in big tins,

With a delicious fragrance that still haunts me today –

I cannot leave a packet of Cheeselets unopened),

But the green was great for playing football,

While on Saturdays you could go on the Loop,

A train that ran from Swindon Junction to Old Town,

It cost a tanner and was a train spotter’s joy,

Steaming slowly past the railway works,

Past all the locomotives in for a re-fit,

So many train numbers all so quickly,

You had to shout them out as fast as you could,

While your brother scribbled them down as fast as he could,

In a desperate attempt to match

The gathering speed of the train,

Until you reached the other world that was Old Town,

A rather more sedate and conservative Swindon,

Despite its Locarno dance hall:

A Betjemanesque country town atmosphere,

A slower pace of life – refined, genteel –

Up the hill by the Town Gardens,

Even the fish and chip shop seemed posher,

While the Old Town station was an enthusiast’s delight:

Victorian refreshment rooms,

A train to Marlborough Mop fair,

A holiday line to the south coast,

Or you could watch the coal carried to Moredon power station,

Or catch alien train numbers at Rushey Platt,v And feel as though you really were in the country,

Buddleia and rosebay willow herb all around;

When you got back to Swindon new town,

You could go to the Spot or Hobbies Corner,

To buy airfix kits of spitfires and hurricanes,

Walk past the old railway hospital,

Where your brother went when he got an arrow in his eye,

When playing cowboys and Indians,

Have a swim in the Milton Road baths,

Walk home past the water tower,

Through the railway park,

Where your mum would tell you about the old days,

When the GRW fete,

Featured a giant lardy cutting machine,

That cut the giant cake by steam,

Or you could make friends with all the American kids,

Sons and daughters of the so many airmen,

From Fairford cold war air base,

Who lived near us, and took us to the base,

For the Bugs Bunny cinema and Hershey’s confectionary;v Or we could go to the cinema in town,

Throw stink-bombs at the Saturday morning flicks,

Watch a skiffle band start the show at the Savoy,

Or go to the Gaumont, there must be a war film on there,

Or out of town, see Rob Roy at Rodbourne Cheyney,

Or go to the fleapit: the Classic in Gorse Hill;

You could chop down trees in the autumn half term

For the street bonny on Bonfire Night,

Roast potatoes in the dying embers,

Play ‘follow my leader’ over and along the brook,

Play football in the street

But be too frightened to ask for your ball back

From the rebarbative Mrs Bristow,

Be hung over the side of the iron bridge,

Mrs B’s son, Godfrey, hanging on to your feet,

Braying with laughter,

While your six-year old self stared straight down the chimney

Of a King class express train,

Initially fighting and struggling,

Shouting and screaming,

Until, catatonic with fear,

You counted the carriages one by one until danger had passed,

Until, at last, you were hauled, trembling, back up by Goff,

He, braying still with laughter,

Others staring, wordlessly, slightly aghast;

But you could get your own back when the clocks went back,

By playing knock door runaway,

Repeatedly, at Mrs Bristow’s house,

Just when they were having their tea,

Or you could step out into the street,

On a starlight New Year’s Eve,

And listen to the concert of whistles,

From all the drivers shunting on their shift

At Swindon station, sidings and railway works.

You could listen to the ventriloquist on the wireless,

You could watch your dad build a television set,

It looked good in the shed but blew up in the house,

You could sit on the arm of a chair,

Pretend it was a horse and you were the Lone Ranger,

When at last you got a proper telly,

You could think that Swindon must be really important,

Cuz when you went on day trips to Weston or Weymouth,

Everybody else seemed to come from Swindon too,

You could think that suburbs of Swindon,

Like Upper and Lower Stratton were proper rural villages,

Especially when out the back at the Wheatsheaf,

Sipping Vimto (anagram of vomit) in the dark,

Absent-mindedly eating blue bags of salt,

Gathered from out of your bag of potato crisps,

Pressing your face against the small window,

That opened a light into the public bar,

Where all was high spirits and sing song,

And where grown-ups seemed to be behaving

In a most un-grown up way;

You could get stuck in the mud and the marsh,

When they were building Pressed Steel,

And feel threatened, isolated, and alone,

Not because you were slipping into the oozing mud,

Seemingly far from home with not a soul to be seen,

But because you somehow knew

That this new factory – cars not trains –

Pointed to the end of the reassuring world you had known,

The end of early childhood,

The end of the 1950s,

The end of the beginning.

Stuart

Stuart