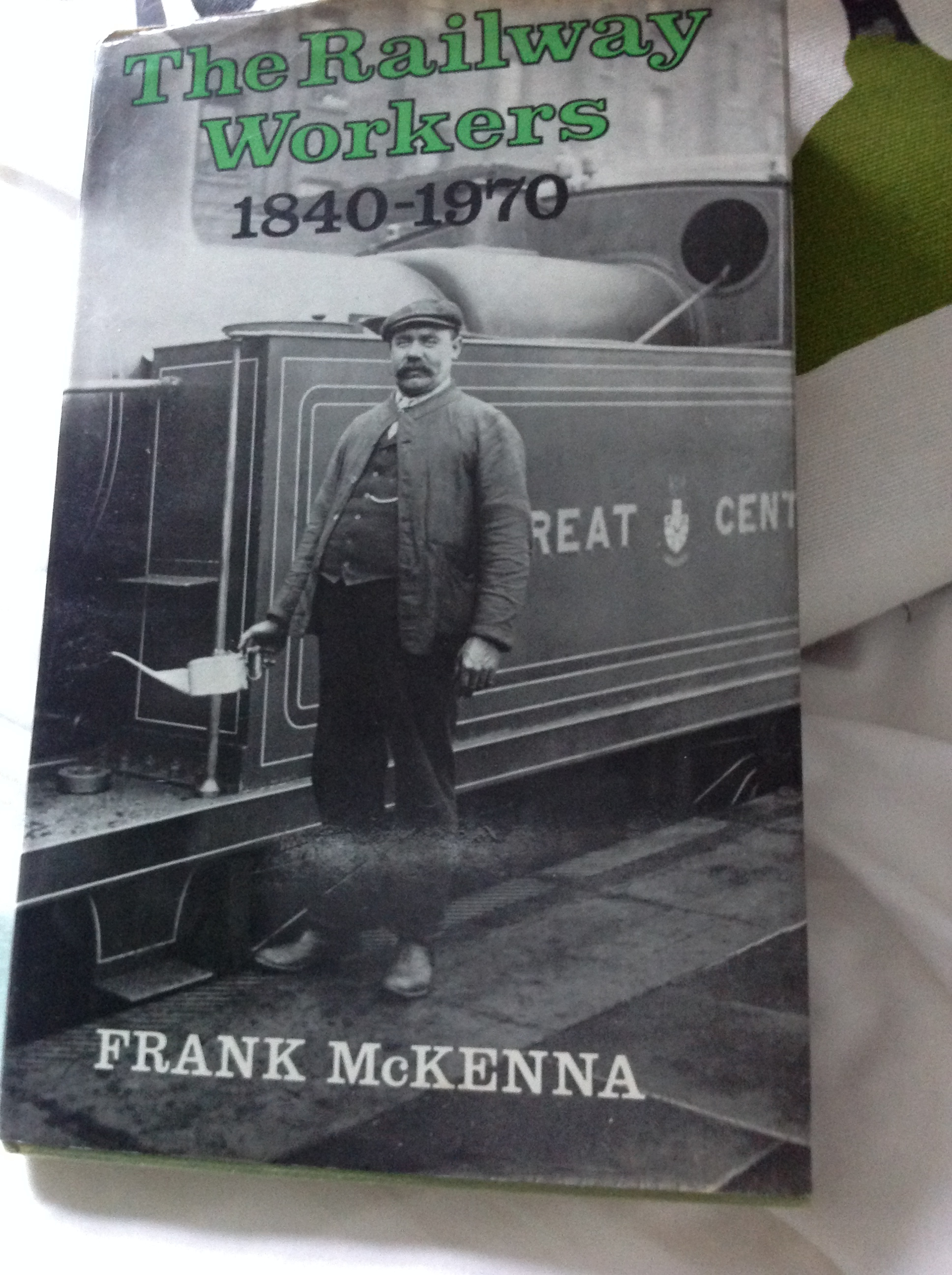

According to my History teacher,

The first railway casualty

Was William Huskisson,

President of the Board of Trade,

At the opening in 1830

Of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway,

Who, before expiring, called for a quill,

To dot the ‘I’ in his signature’ -

And, so become an unwitting exemplar

Of fastidious grammar school punctuation,

For Mr Comrie and his pupils.

In fact, the first casualty was an unnamed labourer,

Blinded by the gun that saluted

The arrival of the Duke of Wellington,

And, so he became an anonymous precedent

For all those who tunnelled, cut,

Bridged, bricked, shovelled and steamed,

Past canal, coalfield, hayrick, slum and factory,

Past siding, shed, semaphore and signal box;

Countless navvies, men and women

Who plate-laid Britain’s industrial and imperial power.

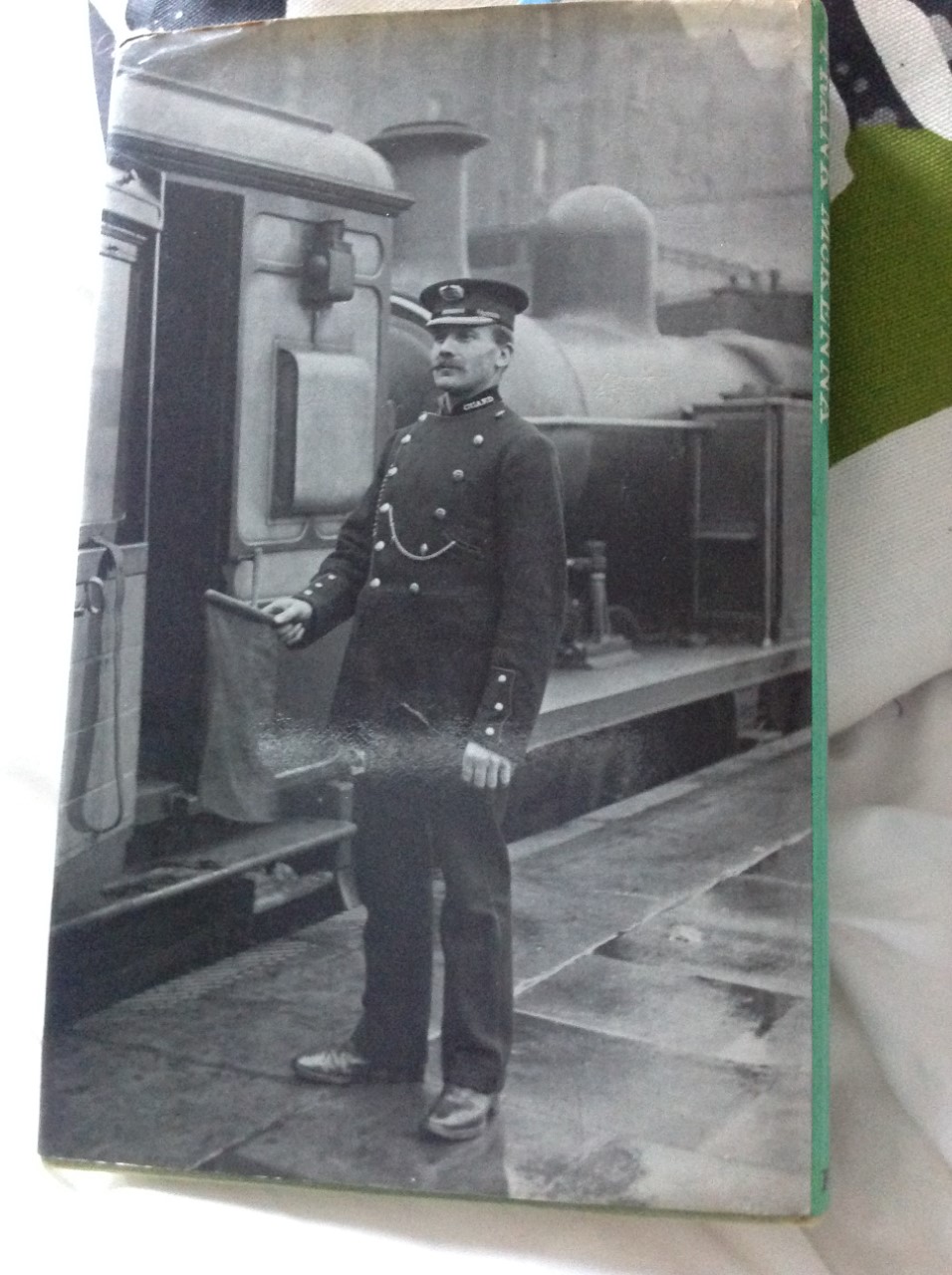

And then half a million men and women,

Subject to rule book, log book, low pay,

And an inspector’s martinet order;

Company-clad in uniform,

Disciplined by livery and temperance,

Samuel Smilesian self-help,

And by tied housing,

And the dead-man’s shoes

Of Railway Time.

And, so it was, a generation before

An education act provided free schooling,

The Great Western Railway would ask

Cap-in-hand aspirants applying for a job,

To provide evidence of literacy,

By copying out this maxim:

‘Zealously try to excel.

Industry is commendable.

Perseverance deserves success.

Quietude of mind is a treasure.’

Can you imagine any maxim More quintessentially Victorian?

A world of gaslight, back to backs, and the workhouse;

The engine shed, the ash pit;

Night black platform,

Coal fired waiting room,

Leather strap carriage window;

A world of a proud aristocracy of labour,

But also victimised trade unions,

A world of signalmen clanking levers,

And tip-tapping the telegraph,

Filling in the forms in triplicate,

Polishing the brass,

Trimming the wicks,

Cleaning the grates,

And all for sixteen bob a week,

On a sixteen-hour turn;

A world of pointsmen and fogmen,

Choking on the fumes of a pea soup fog,

Kindling the coke in the brazier,

Banging up the wagons to pilfer some coal,

While winter’s frost and a cold, clear moon

Light up the permanent way.

Then at five minutes past midnight,

The goods guard’s tail van leaves the marshalling yard -

Hectic with wagon examiners,

Repairers and axle box greasers –

And its red tail lamp slowly disappears

Into the reverberating distance,

While he sits alone in his van,

In dark isolation,

Buffeted by shunting, points and engine brake,

Watching the night slowly tick away

In silent loop or siding,

Counting the pennies of overtime,

Hoping for passenger-promotion,

Lighting another Woodbine,

Staring at the moon:

Railway Time.

But down at the running shed

All is different!

Hustle, bustle and red-hot tumult:

Fill the tender! Water the tank! Empty the firebox!

(Cough on the dust, choke on the fumes, burn your hands.)

Smash the clinker! Draw the firebar! Sweep the pit!

(Hot sweat pours down night-cold skin.)

Rake it out! Open the damper! Push it through!

(And rush outside for a lungful of frost-fresh air.)

Clear the smokebox!

Four whole barrowfuls!

Race against time!

Steam pressure’s falling!

Something’s awry!

Repair the brick arch!

Firebar setter!

Boiler tube cleaner!

Where’s the fire kindler?

Dreaming he was a fitter

In the quiet order of the fitting shop,

Or a roster-clerk, dozing after tea

And cribbage in the mess room.

But there’s no escape, even in dreamland

From the foreman’s peremptory demands:

Cover the inkwells!

Use both sides of blotting paper!

Save on lighting!

It’s a full moon!

Or perhaps he was dreaming of the footplate?

That long, long, lifetime ladder

From cleaner to fireman to driver,

Starting out with rag and oil and grease,

And soot and paraffin and tallow fat,

And sulphur and ash and blistered hands,

And all for thirteen bob a week,

Unpaid overtime,

and a seventy-two hour week.

But now he sits, chatting and listening,

Drinking tea with the tired eye drivers,

Who now sweep the floors and clean the lavs;

And they sit, tired eye, and declining,

Remembering their footplate days,

Slipping and sliding from mainline shifts,

To shunting and siding;

And as they doze,

They recall their footplate youth,

Walking in the driver’s shadow and footsteps

(Behind his black box, overcoat and rule book),

Proud of a brand-new billy can

And a brand-new blue serge jacket

(No cleaner’s overalls now),

Arriving early to prepare the engine,

And the driver’s seat, and the boiler pressure,

And the water level,

the firebox and the fire;

Until, freezing in the cab, paper in his boots,

He gets stuck in a wind-whistling loop,

Out here in some unsheltered, open landscape;

Or, shovelling six tons of coal,

Choking in some seeming endless tunnel,

On a two-hundred mile journey

Of relentless, endless standing,

Shovelling, shovelling, back-breaking labour,

Watching and checking and checking and watching,

Until the journey ends, lodging away.

He had left home early in the morning,

A stranger to the children;

A weekly pay packet to the wife;

Waiting for the proud longed-for day,

When he takes control of the regulator:

A right proud member of ASLEF;

But now he’s on another interminable shift,

Freight train working in the dead slow of night,

Catching a moment to dream his future:

Mainline passenger link,

And the top pay packet each week -

When name, engine and coal consumption

Will be systematically monitored -

Renting a house close to the lodge,

And close to the marshalling yard,

With double-homers to boost his wage;

A spring time step in his walk to work,

On past the gas works, the pub and the chip shop,

A wriggle of his hips as he walks by the football pitch,

With egg and bacon for a fry-up on the shovel;

But back in the house, she sits fretting.

Is this the time he crashes?

Her anxiety worsened, her nerves on edge,

After a twenty-year marriage

Of sleepless fatigue and shifting shifts;

Twenty years of keeping the kids quiet,

And the door knocker muffled:

The Railway Widow;

Sleepless, cold, and alone, in the double bed,

While he tip-toes across the lino,

Gently closes the front door,

And trudges off for the 2.15 link,

Shunting in the sidings,

Feeling his eyesight failing:

Railway Time.

Dead man’s shoes.

Stuart

Stuart