The boy who wanted to be a STEAM TRAIN DRIVER

It’s 1965, a bright summer’s day, and the boy is sitting in the schoolroom thinking about the future. He’s wearing a hand-knit jumper that his Grandmother has made, a white school-shirt, and grey short trousers that are making itches on the skin of his thin thighs. He’s got his elbows on the desk, his chin is resting in his cupped hands and he’s dreaming. He’s not paying full attention to the teacher, as the class is slow-moving and he’s a reasonably bright kid.

And he wants to be anonymous. He sits slightly nearer the front than the back. He doesn’t want to sit at the back with the naughty boys. He doesn’t want to sit at the front with too much close attention from the teacher. He doesn’t want to sit right in the middle as he’d feel trapped with no escape route. So he sits towards the front and towards the side, participating in the class, but not in a conspicuous way.

He’s soon going to be ten years old and it’s dawning on him that he won’t be at school forever. One day, he’s going to grow up. And have a job. He can’t imagine either.

Sitting on the north side of the room, the boy is looking out of the large windows onto a playing field, and beyond that is an exposed railway embankment. It’s twenty feet high, and forming my horizon right across the flat landscape of the Thames Valley, fifteen miles from the buffers at Waterloo; specifically the length between Walton-on-Thames and Hersham.

I now know it was originally part of the London and Southampton Railway, the section outside my school being opened in 1838. Now, in 1965, it’s part of British Railways Southern Region mainline, from Waterloo to Bournemouth, the last mainline passenger services in Britain to depend on steam locomotives. I knew nothing of this at the time. The limit of my understanding was that London was in one direction, and the seaside was in the other.But what I did know was that all I wanted to do, was to be a steam-train driver.

The high railway track outside the window was straight, level and distant from major stations, so the dirty locos were running flat out at 60, 70 or 80 miles an hour. It was a wondrous sight, seeing the smoke and steam plume, hearing the roar of the hard working engine, watching the express train zoom across my boyhood horizon.

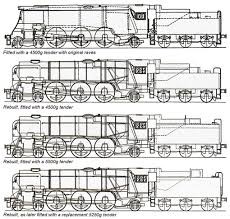

There were Bulleid Pacifics, large and very large. Some had box shapes. They all had long rakes of carriages.There were Bulleid Q1s pulling goods trains, an austerity design with a boiler that had the outward appearance of a telescope. And there were older slower locos, 2-6-0 Moguls built by various Chief Mechanical Engineers. And lots of EMUs, (Electric Multiple Units) that didn’t really hold my attention, as they quietly and efficiently went about their suburban passenger work.

I was ten years old, and, if I thought anything at all, it was that all things would carry on just as they were, forever. Yes, I’d grow up, but the world would remain the same.

It would still be me, but much taller and with a bristly chin like my Dad’s. I’d be wearing long overalls and a cap, passing through Hersham on the footplate, and looking into the school windows, and waving at any pupils looking at me. I’d be travelling at seventy mph, shovelling coal into the firebox, in between slurping tea out of an enamel mug. I’d be driving the train, subtly adjusting the steam engine controls and levers, tapping the dials, tweaking a valve, leaning over to check if the railway signal is up or down, and tooting the whistle.

My career plans didn’t unfold as anticipated. All steam traction was gone in a couple of years, and our family moved away, to the East of England. Decades later I ended up working in Multi-Modal Transport Policy, however that’s another story. But whenever I smell steam and coal smoke I’m instantly transported back to my junior schoolroom, thinking about the dreaming boy.

Andrew

Andrew